A MEMOIR

Alfred John Vincent Ramage was the only child of Stanley John Ramage, 1875-1912, a fire insurance clerk, and Constance Minna Ramage, nee Wortz, born 1874. His was a tragic story of disappointments, rejections, achievements and failures, yet he raised and educated 4 children, with reasonable success. This memoir is an account of what is known about his life. He spoke very little about his origins, some of the facts are only now coming to light. I decided to set down what we know, with a sprinkling of speculation, so that any grandchildren and great grandchildren who are interested may learn about their extraordinary ancestor.

His parents

The Ramage family had come to UK from France in 1789, just as the French Revolution was gathering strength. They settled in South East London, and there are Ramage graves in Nunhead Cemetery, presumably members of that family. They were not well to do, and took quite lowly employment. There are some distant cousins known who may have continued the line.

His mother was one of 5 siblings, 4 daughters, 1 son, whose parents were respectably established and comfortably off. Their father, Charles James Wortz, was a respected doctor in Fordham in Essex, where they lived in a substantial house, Fordham Lodge. The son Edwin, John’s uncle and another doctor, was married and lived nearby at Penlan Hall with his wife and son Ian.

Constance Minna Wortz married Stanley Ramage in June 1903. John was born 2nd January 1904, at 5A Loxton Road SE23 2ET, registered in the Lewisham District records and baptised 3 years later. They also had a daughter, Marjory Inez, born 2nd May 1905 who died age 2, and a son, Alfred William, who died in infancy.

Their father, Stanley, died in 1912, but by then John’s mother had disappeared. Rumour had it that she ran away with a lover many years before, but there is no record of this! (** see footnote) It seems likely that it was after his father’s death, at age 8, that John joined the Wortz family in Fordham, maybe there were no other relatives available or willing to take care of him. A lost tinted photograph of John dressed as Lord Fauntleroy may be presumed to have marked the occasion.

Early Years

Once John came to Fordham, he was raised by his 3 aunts along with his cousin of similar age, Ian Wortz. Ian and Jack, as he was called in the family, became close friends and remained so all their lives. Although very different in character and looks they behaved like brothers to each other and valued each other highly. John, being an orphan with a disreputable and vanished mother, would have been an outsider in his own family from the start. I do not believe John was loved or wanted by any of them, although one of the aunts, Netta, referred to him in a letter as “Little Jack” when he was 12. He was indeed small and slight for his age.

Education

John was educated first at Colchester Royal Grammar School, a renowned institution, founded in 1128, awarded royal charters by Henry VIII in 1539 and Elizabeth I in 1584. His grandfather then enrolled him at Christ’s Hospital. This school was founded in 1552 by Edward VI “to provide food, clothing, lodging, and learning for fatherless children”. The school moved to Horsham, Sussex in 1902 which is where it was when John entered it in 1916. He was enormously proud of that school, spoke about it often with gratitude and affection, and remained in the old boys club until he died. His relationship with the school probably provided the consistency and stability which had been lacking in his early family life, and it gave him a sense of belonging which had been absent from his home. There was also an element of theatre about the school uniform which appealed to John.

He yearned to be a doctor, but his aunts refused to fund his training. His cousin Ian Wortz went to Cambridge to read medicine and left after one year to breed horses, which was his true calling! John had excelled in maths and science, ideal for the study of medicine, but that was denied him. John was never heard to comment on the unfairness of his treatment in this.

Early adulthood and WWII

After he left school at age 16, the 1921 Census records him living at Fordham Lodge with his grandfather, Charles Wortz and aunts and working as a Stock Exchange clerk for Dennison Seal and Dale at Swan House, Moorgate, London. I know nothing more of his life and career until the mid 1930’s when he met Jessie May Harris, the love of his life, whom he married in December 1935 in Ipswich. She worked in office jobs to support him as he pursued his studies to become a lawyer. They struggled financially, and were never well off, but managed.

At the outbreak of war he joined the Royal Navy Volunteer Reserve. During the war he claimed that he served on the North Atlantic convoys, a very dangerous mission. He had a serious mental breakdown and when he recovered he was given a desk job in Intelligence as Temporary Lieutenant, Naval Reserve shore-bound from 10th June 1941. Records show that he had undertaken special training for this role, and he was then transferred to the Press Division in May 1943.

Family Life

During times ashore and after his breakdown the couple bore 3 wartime children, Susan, 1939, Richard, 1943 and Philip, 1945. Another child, Prudence came later.

The family lived in Ampthill, Bedfordshire, then Kenton, Middlesex, and when Richard won a scholarship to Colchester Royal Grammar School in his father’s footsteps, they moved there, to live at 2 Athelstan Road. Philip joined Richard at the Grammar School as soon as he was old enough. There was never much money, but there were hopes of an inheritance when the last of the elderly aunts died, but this unfortunately never materialised.

John was intensely proud of his children, particularly Richard, who was the shining one. Susan went on to become a nurse at the Middlesex Hospital, Philip and Richard both enrolled as medical students at Guy’s, and qualified successfully, Prudence found her niche once she went to Australia, trained as a nurse, and showed herself to be just as bright and talented as her siblings. John revelled in hearing stories of their various exploits, and would boast about their achievements to anyone who would listen.

After the children had all left home, he and Jessie moved to Higham in Suffolk, where the only social life was in the pub across a dangerous road, their house was on a corner. Jessie missed her friends and her connections in Colchester and never seemed really at home in Higham. John gave his time to the garden and to birdwatching, but both seemed to be making the best of a bad job.

His career

Although qualified as a lawyer by 1939, his war service delayed him establishing himself professionally until it was over, but then he set up a practice as a criminal defence lawyer in Stratford, East London. He became well known and respected in the area, police and criminals would greet him in the street. I formed the impression that there was an element of a game between the police who had to catch the villains and build up a case, and the lawyers whose job was to get the villains off, frequently by finding faults in the case presented by the police. John used to enjoy recounting his delight when he had unearthed an error in fact or paperwork that meant he could get his client off.

The breakdown he suffered in 1941 was the first recorded episode of the depression which dogged him for the rest of his life. He was twice admitted to hospital, and had ECT twice. This is an indicator of how serious his condition was. He had surgery for prostate cancer in 1967, and whilst recovering from that his business partner took over his practice and sabotaged his return. According to the London Gazette, the business was finally wound up in 1970, and he was left almost destitute without work or funds. This prompted another bout of depression.

He was now 66 and without a legal practice of his own but managed to survive as a locum and with temporary jobs. Then in 1968, he made an extended visit to Australia to see Susan and her husband Colin, an anaesthetist, and her first 2 children Elizabeth and Jennifer. As time hung on his hands he decided to read for the New South Wales Bar, which he achieved in 6 months, and on his return to London, took pupillage and read for the UK Bar.

He was over 70 when he qualified and was called to the London Bar, and he loved being a barrister. The drama and excitement of it suited him, and for just a few years he had the energy and drive to travel from one court to another all over the country, reading his briefs and making preparations on the train journey.

By 1975, he was feeling his age, and had stopped enjoying the work. He had lost his energy and verve, and had made just enough money to retire, so that is what he did.

His Character and Personal Qualities

One of the most striking elements of John’s personality was his fierce intelligence, something he passed on to all his children without doubt. He was intellectually curious, willing to take on the new ideas that appealed to him, a fast learner where he was interested, and rigorous in his logic and arguments. He was probably an excellent advocate.

Emotionally labile and very sensitive, his kindness was endearing, but he was not an easy man. He could be demanding of attention, and sought it from women for whom he had a special liking, and with whom he could form warm liaisons. I do not think he was a womaniser, but he saw himself as a ladies’ man. Maybe it was fed by a desire to try to replace the mother he lost at such a young age.

John was short, and over a lifetime this made him pugnacious, a useful quality in a barrister in a court of law, not so easy in a family man. Socially and with his family he had a tendency to dominate, but as a conversationalist he was entertaining and interesting. He had a temper, not that I ever saw it, and was prone to bouts of serious depression which were a strain on the marriage and very debilitating.

He fell into one of these pits after he learned that the two aunts, from whom he had great expectations, had disinherited him. This was a huge blow to him, and although he put himself back together, in some way it affected him and his trust in people for the rest of his life. He let it be known that the cleaner who inherited had probably added more to the lives of his aunts than he ever did, but was deeply hurt.

From time to time he would spend a night with us as he passed through London, exhausted but full of stories. He was a most appreciative guest, although he would fill the downstairs rooms with his things, umbrella and bowler hat dropped in the hall, gloves and coat somewhere between hall and living room, where the brief case would occupy one chair and he would occupy another. Richard would then gather them all up and dump them somewhere else.

He had plenty of energy into his 70’s, it was his mental health that was always vulnerable. After Jessie’s death in August 1977 his life became purposeless and unbearable to him, and he shot himself about 9 months after she died, having visited the local publican and his wife to say goodbye, and alerted the Ipswich police to save his children from being faced with his remains.

His faith.

John was a convert to Roman Catholicism and had joined the church just before Susan was born in 1939. It meant a lot to him, he liked the drama, the incense, the sounds, the latin text. All the children were raised in the Catholic faith, they were educated at a Catholic Primary School in Kenton during the family’s time living there. Susan married in the Catholic Church in Soho Square and was the only one who remained a catholic for the rest of her life.

When the Vatican Council voted to stop using latin in its services, John was horrified and for weeks could talk of little else. He went through a crisis of faith and eventually left the church and never went back. Jessie’s funeral was held in the Church of England Parish Church in Higham in Suffolk where they were living by then. His own funeral the following year also took place there, as did Richard’s in 2003.

His interests

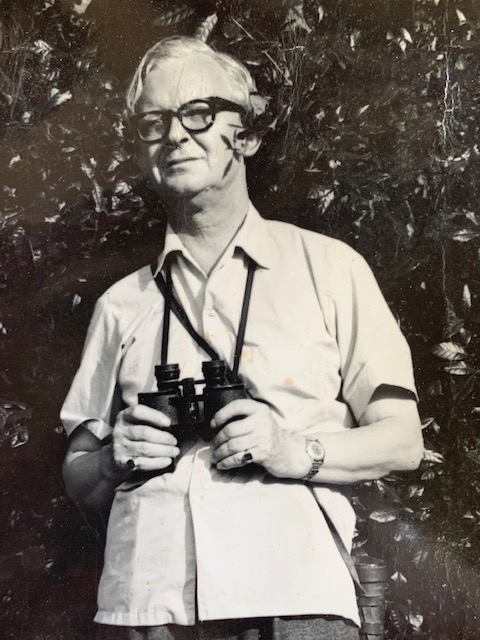

He was a very well informed and respected ornithologist, and would spend many hours with his friend, Joe Firmin, wading through cold, muddy fields in horrible weather to catch a glimpse of an unusual winged visitor, or whatever wildlife phenomenon had captured their attention. Joe was a writer on a local newspaper and had a regular column to fill, so their exploits were sometimes material for what he was producing that week. They were good friends, John did not have many confidants, but Joe was one of them. They visited the Carmargue one year, a very special trip that John cherished.

During his long visit to Australia in 1968 he enjoyed birdwatching safaris with his son-in-law, Colin Orr, who knew where to take him and who to introduce him to. Colin was somewhat of an amateur ornithologist himself, but was outshone by John’s prodigious knowledge. John’s account of this visit makes fascinating reading for anyone interested in birdwatching and is appended to this memoir below.

His other passion was his children. I think they and Jessie gave a meaning and purpose to his life, in the way the Church had given spiritual meaning. He would boast outrageously about their achievements, and exaggerate their importance. I became included in this when I joined the family as Richard’s girl friend soon to be wife. On one occasion I was introduced as a theatre sister which was complete nonsense, I was terrified of the operating theatre and was a humble staff nurse at the time.

He was curious about how we all thought and what we were interested in. He was the first grownup to ask me my political opinions, which I actually did not have, no-one had ever enquired before, so I fluffed something which satisfied him and realised I had better educate myself. When he thought I was interested in Buddhism, as many of us were in the 60’s, he wanted to know more about that and read “Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance” to inform himself, and told anyone he could that I was a Buddhist, again, not true!

He was also a bit of a gardener, he and Jessie did not always agree about garden plans. When she travelled back from Australia by ship one year, he had spent time enhancing the garden to please her, but on her return she was not pleased and moved or threw away all his planting. By this time the marriage was no longer going well, for some reason she had turned away from him and could no longer love him as she had. He could do nothing right or pleasing to her although he remained devoted to her.

The End

After Jessie’s death from pulmonary emboli, in St George’s Hospital, Tooting, there because she had been staying in nearby Balham through August 1977 when she was taken ill, he never recovered any pleasure in life. His grief was inconsolable and he became profoundly depressed. By 1978 his life felt purposeless and unbearable to him, and he shot himself about 9 months after she died.

He left behind a family of 4 children, 10 grandchildren and now in 2020 quite a few great grandchildren. I write this in case any of them are curious about their Ramage inheritance at any time. He may have passed on intelligence, courage, sensitivity, good health for which they might want to honour him, and emotional vulnerability with which they may occasionally struggle.

**Constance Minna Ramage, nee Wortz

She was living at Lyham Road Brixton in 1951, so presumably had not returned to her family in Essex, and they did not acknowledge her existence if they knew of it. Records seem to indicate that in 1964 in Chelmsford she married Ernest J. Belcher, 1910-1969, a man 36 years her junior. His death was registered in Lewisham.

Appendix I

An Ornithologist in New South Wales

John Ramage, M.B.O.U.

From London to New Delhi

In March 1968 I flew to Sydney to visit my daughter Susan and her husband and their family. I was hoping to have a unique ornithological experience and there is no doubt that I was not disappointed.

There are approximately 700 species of birds in Australia so before l left England I wrote to a friend in Alice Springs then doing research for the British Museum. He sent me check list of the birds of New South Wales to try to limit the field. The list showed that there are over 500 species in the State of New South Wales alone.

I took off by BOAC from Heathrow Airport and the first daylight landing was at New Delhi which is both a military and civil airport. The sky was dotted with vultures and kites of various sorts soaring on the thermals. This particular airport is both civil and military under the control of Indian forces who are very strong on security and take the worst possible view of strangers with binoculars

I left the other passengers to have a better look at a dark bird sitting on a telegraph wire. It was like a small jackdaw with a very long tail sharply forked and curved towards the end, and was a black drongo. I had some difficulty convincing a turbaned sentry complete with rifle and bayonet that I was only a birdwatcher and he escorted me firmly back to the plane, which was consequently delayed for some minutes.

Overnight in Singapore

I stopped off for 24 hours in the sweltering heat of Singapore, spent the night at the Raffles Hotel where after an exotic dinner served under the palm trees by candlelight I slept soundly for 14 hours. The next day I visited the Botanical Gardens where I saw various strange birds, which included swifts with white rumps and Indian mynahs. Here the European tree sparrow seems to have taken over from the home sparrows and are so tame that they come to the tables where people are eating and pick up crumbs that fall. I left Singapore by Qantas at 5.40 pm landing at Perth at 2 am.

Arrival in Sydney

When I eventually arrived at Sydney I found it to be a most beautiful city, built entirely around an enormous blue water harbour with great creeks extending in all directions like starfish. The suburbs are surrounded by bush which invades the city at various places, and is really an extension of the endless eucalyptus forest coming down from the surrounding hilly or mountainous country.

The lovely suburbs of Sydney are teeming with bird life and even in Autumn the verges are lined with wild flowering shrubs. In the garden there are kookaburras, mudlarks, cuckoo shrikes, and butcher birds, vivid rainbow lorikeets and Eastern rosellas fly rapidly across the sky with high pitched screams. These lovely red, yellow and green parrots feed on eucalyptus flowers and share the fruit laden peach trees with the currawongs. The currawong is a big rook like bird but is not a corvine and has a white patch on its rump and at the end of its tall.

Birdlife around Sydney

On the many creeks and streams various gallinules abound, such as moorhens with red legs ,and big purple coots with red-crowned head shields. Spur winged plovers walk about in the parks undisturbed by passing cars. The most ubiquitous urban birds are the noisy miner (soldier-bird) and the Indian mynah. These birds are not in any way related. They roughly take the same place as starlings and blackbirds do in England. One of the many tree swallows, known as the welcome swallow, closely resembles our English bird, except that it lacks the black band across the chest and has rather more red on the forehead.

Sydney harbour is fairly rich in birds. The majority are silver gulls which are about the same size, and closely resemble the English black headed gull, save that they do not have the dark head. A striking feature of this gull is the completely white iris with red eyelids and scarlet beak. I saw Arctic skua, and cormorants of many different sizes and colours and also the crested tern – a large bird 19 inches in length.

Conservation is keenly practised in New South Wales and large areas of bush are dedicated to reserves which teem with birds. These include the red and lesser wattle birds, shrike tits, thorn-bills, yellow robins, yellow eyes, willy wagtails, red browed finches, honey eaters, and brilliant blue wrens, together with scores of very small birds difficult to identify. Dusky weed swallows in small groups hawk for flies from dead branches of trees. Wood swallows are in no way related to the European hirundines and in flight are like the waxwing. They are brown and white with strong bluish beaks, similar to the English chaffinch.

Towards the Blue Mountains

My son-in-law, Dr Colin Orr, a competent and cautious observer, took me to many places to see fresh birds. At Yarramundi Lagoon, approaching the foothills of the Blue Mountains I saw the black tailed water hen which closely resembles a moorhen but has a green head shield. Here I saw the brown hawk, which is the everyday predator of Australia and also a small white hawk, known as the black shouldered kite. As the trees grew denser towards the great forest covered hills overlooking Emu Plains, the bell-bird, a bright green honey-eater, with a pinkish bill, swarmed in the trees feeding young. The green plumage of this bird made it difficult to see at first, but the incessant noise of its high-pitched voice fills the air with a sound resembling the squeak that is made by binding car brakes. To such an extent is this illusion effective that even Australian motorists have been known to stop their cars to see if in fact something has gone wrong with their brakes.

One of the most exciting and dramatic sounds of the bush is the voice of the whip-bird. This dark green bird with striking white cheek patches and a jay like crest is about the size of a blackbird and shape of a European magpie. Its call can only be described as the crack of a coachman’s whip. The bird skulks in the shrub and according to the text books is rarely observable, but as a reward of endless patience we managed to get good views of this beautiful creature on several occasions

In the grounds of the Seventh Day Adventist Hospital – one of the finest hospitals in Sydney – I watched the broad-billed roller or dollar-bird hawking for insects in the dusk. This bird – the only Australian representative of the roller family – flies heavily like a woodcock. It gets its vernacular name from the large silver spot on its purple wings below the carpal joint, which gleams like a silver coin. Its habits are largely crepuscular so its lovely plumage and red bill are difficult to observe.

Staying in Terrigal

Dr Orr and I spent 4 days at a delightful bungalow – lent to us by Mr and Mrs Taylor of Pymble – at the small weekend holiday resort of Terrigal, in the bush on the pacific coast about 60 mile north of Sydney, which is an ornithological paradise. Here, standing on the Skillion rock peninsula jutting into the sea we saw the wandering albatross flying over the surface of the Pacific Ocean below us. We also saw white-breasted sea eagles as well as various herons. A few mile away at Tuggerah Lake, wild black swans were swimming with their cygnets and on the muddy banks of this vast waterway were plumed and white egrets, as well as many Asiatic golden plover and bar-tailed godwit. These were in breeding plumage and were clearly waiting to start migration across the Pacific and up the west coast of America to the Arctic tundra to breed.

Bouddi National Park

After surf bathing at Maitland Bay in Bouddi National Park I was lying on the sand to dry off in the scorching sun when a huge wedge-tailed eagle glided overhead quartering the cliff for prey. Here it is commemorated that on the 5th May, 1898, the paddle steamer “Maitland” with 60 persons on board, was wrecked in a gale. After two hideous nights 26 people managed to get ashore with a rope. Landing on the rocky beach they were faced with miles of uninhabited bushland as their only shelter, nevertheless the captain and a small child were among those saved. I was able to photograph the rusting boilers from the ship still lying nearly a hundred years later amongst the vast boulders which had fallen from the top of the cliffs surrounding this beautiful bay.

Jenolan Caves in the Blue Mountains

A few days later we visited the mysteriously beautiful Blue Mountains which lie about 120 miles to the west of Sydney. These mountains, as one approaches them from a distance are indeed a rich deep blue. It is probable that they get their colour from the reflection of the leaves of the millions of eucalyptus trees with which they are covered. We stayed in the Blue Mountains at a government hotel provided for tourists who wish to visit the Jenolan Caves. These caves are one of the wonders of the world, as it is possible to wander underground for miles through dark caverns full of stalactites and stalagmites, underwater lakes and streams.

The whole exercise is highly dangerous in spite of having an adequate lighting system; even so the visitor has to climb many perilous flights of steps, some cut in the stone and some just bare vertical steel ladders provided by the authorities to make the journey possible. The whole phenomenon is similar to the Cheddar Gorge, but on an immeasurably larger scale. My daughter was expecting an addition to her family so we could only manage to explore one of those caves known as the River Cave, and it was hard going for two hours.

Away from the Blue Mountains

After leaving the Blue Mountains and passing through flatter and more pastoral country, I saw a flock of galah cockatoos alight on a tree. These lovely birds are pearly grey with pink breasts. When the flock settles down It looks for all the world like a magnolia tree in full flower.

The bird life of Australia is absolutely fantastic. In the bush there were hundreds of very small birds constantly moving about, many of which were so small that it was quite impossible to identify them. One difficulty of Australian bird study is that the nomenclature is apparently contradictory. The big black and white but short tailed magpies, for example, are not really corvines but are a genus of shrike confined to Australasia, as also is the butcher-bird which is not in the least like our butcher bird. It is the size ands shape of a jackdaw but it is coloured grey and black and the tip of the bill is hooked. Surprisingly enough it has a most melodious voice, and is regarded by Australians as their most beautiful songster. The cuckoo-shrikes are distantly related to the old world fly-catchers.

Avian Nomenclature and Joseph Elsey

I can only assume that names like “cuckoo-shrike” and “magpie” came to be used because when the first settlers arrived there were no ornithologists so they used these names because of the apparent resemblance of the birds they encountered to those they had left behind in England. It was not until 1885/6 when Joseph Elsey, a young surgeon from Guy’s Hospital was appointed naturalist to Gregory’s North Australian Exploring Expedition, intended to lay open the interior of the continent from the Victoria River to Brisbane, that some real scientific taxonomy was attempted. His considerable discoveries were hampered by serious ill health and much of his excellent work was lost or destroyed. He eventually died from tuberculosis in the West Indies.

Another problem is the extraordinary number of species within the various groups. There are approximately 65 different kinds of honey eater, 10 swallows, 18 thorn-bills and 21 so-called robins as well as about 12 sorts of wrens, many clearly not related to each other at all. This makes the field identification much harder for the European visitor. Some male wrens reach breeding maturity before assuming the brilliant adult plumage.

I only had the opportunity of seeing a very small quantity of what was available and certainly only understood part of what I saw. Nevertheless, during my visit I did manage, by diligently studying the text books, personally to identify 70 species.

Animal Life in New South Wales

The only wild animals which I saw were two opossums with young in the trees at night in the Blue Mountains, though my wife did see a wild kangaroo. Inevitably I saw koala bears, kangaroos, wallabies, dingos and emus, but these were in special reserves.

Australia has a number of poisonous snakes and reptiles. In the Blue Mountains I came across two dead snakes, both about 6 feet long, which had apparently been crossing the road from opposite directions when each had been simultaneously run over by a car.

Australia also has to cope with at least two other very dangerous creatures. One is the red-backed adder, which is small and about the size of the English garden spider, but easily identified by a red patch at the lower end of the upper surface of its body. This creature lives in piles of rotting wood in the average garden; if one should be bitten by it, then death ensues quite soon unless medical aid is immediate and expert.

The other menace is the funnel web spider, a much larger creature, both sexes are approximately the size of a shilling when the legs are drawn in. This arachnid is so deadly that only two persons are said to have recovered from its bite. It is mostly to be found in the bush, but does also come into gardens. I saw a number of these spiders alive in glass jars which were shown to me by a laboratory worker at Eric Werrell’s Reptile Park near Gosford, where they were being used for experiments to find a suitable serum, which so far had not been developed. There is some concern at the small amount of time and money available for this research. The large but harmless tarantula finds its way into every home and is popular as it eats mosquitos. The suction footed little gecko lizards are also welcome in the home for the same reason.

Human Encounters

My visit to the Antipodes was unexpectedly enriched by three personal contacts. Whilst sitting in a cafe in the Sydney suburb of Manley, waiting to embark on one of the ferries across the harbour, I heard my name spoken. On turning round I saw a girl I know and to whom I had spoken in a bookshop in Colchester only a month or two before.

Alec Chisholm

I was privileged to meet the grand old man of Australian ornithology, Alec Chisholm, to whom my son-in-law arranged an introduction. Mr Chisholm, who in 1968 was 78 years of age, started life as a cub journalist on a tiny local paper in the bush. He remembers knowing old men who, in their prime, had taken part in the gold rush and could tell him of the bloody fights which ensued as a result of the labour disputes between the English settlers and Chinese labor.

When I called on Mr. Chisholm in his flat overlooking the blue waters Sydney harbour he was putting the final touches to a book which he has written for Collins of London, which is entitled “The Joy of the Earth” Anyone who gets a copy of this work will find a wonderful story of his early life in the bush. Mr Chisholm entertained me for two hours with the wit and vigour one would expect from the vivid memories and nimble brain of one who has spent a lifetime becoming famous both as a field naturalist and as a journalist. He still continues to correspond with me at intervals.

John Disney

I carried an introduction to John Disney, Curator of Birds at the Australian Museum, Sydney. Mr Disney entertained my wife and I to a wonderful roof top lunch and we had a most delightful visit to this splendid museum. In his personal section, a nice combination of laboratory and library, I not only handled many birds in skins and awaiting preparation, but saw some of the rarest bird books in the world, including a first edition of John Gould’s “Birds of Australia”, a copy of which was reputed to have sold in London for £25,000. I also saw a set of Matthew’s “Birds of Australia”, which is a very beautiful work in several volumes praised in the late 1920’s and probably worth several thousand pounds. Mr John Disney was most gracious and helpful to me and I shall always remember my meeting with this charming scholarly scientist, rugged explorer and practical naturalist.

Books about the Birds of Australia

By English standards, the number of first class ornithological books to be obtainable in 1968 was not considerable but has now increased. By far and away the most comprehensive book is “What Bird is That?” written by the late Neville W. Cayley in 1931 which has passed through several editions and Alec Chisholm is one of the joint editors. It is in every way a splendid book but whilst it purports to illustrate all the avifauna of Australia it suffers from the disadvantage that far too many birds are shown on one page so the illustrations are small with the result that it is somewhat inconvenient for use in the field. There are other bird books by such writers as A and S Bell for beginners, whilst Leach and Morrison is more advanced, and Chisholm writes exquisitely at large about natural history as it affects Australia in general.

In 1967 perhaps the most striking work was “Australian Birds” by Robin Hill. This is a very large work costing about £8, which claims to be comprehensive and fully illustrated. Unfortunately, it contains a number of technical errors, both of illustration and description, which would have been avoided if the enthusiastic young author and artist had longer field experience and had taken more care in the preparation of his material. It is, nevertheless, a book which must be included in the library of those who are interested in birds of Australia. His later work shows great style, accuracy, and polish which is particularity evident in his “Bush Quest” published in 1968.

The Nature of Australians

I should like to return to Australia to continue my observation of the bird population which, for me, would be an unfinished life’s work. I liked the Australian way of life; I liked the Australian people; I found them cheerful and forward looking, with tremendous faith in their country’s future. Those who go to Australia from this country, and then return dissatisfied, seem to me to fail to realise that the Australians enjoy an entirely separate culture, which is in every way suitable to them, if different from our own. Perhaps the greatest single barrier to real appreciation of it is the fact that Australians speak English. If it were not for this they would cease to be regarded by some as “Englishmen who act in a different way” and would be taken at their true value. By trying to understand them better, it would be impossible not to admire them more.

July 1971